Having been the UK's only full-time professional

meteorite dealer for nearly twenty years, I seem to have become the default

British enquiry service for anyone who believes they have found a meteorite.

Although I'm always happy to chat, it is a surprising fact that so many

people phone or e-mail me that answering these queries probably occupies

a couple of hours every week! Furthermore, I cannot recall the last public

event I attended when I wasn't shown a treasured space rock that was,

in reality, a lump of furnace slag or common mineral. Unfortunately, no

matter how gently I try to let the finders down, they quite often become

indignant and, sometimes, even abusive!

I suspect one reason is the success of the American TV series 'Meteorite

Men' which was repeated on 'Freeview' channels a number of times. The

presenters Geoffrey Notkin and Steve Arnold travelled around the world

looking for - and finding - meteorites in something of a Harrison Ford

fashion. Arnold in particular tended to stress the financial value of

their finds: he'd pick up a small brown lump of rock from the desert floor,

turn to Notkin and come up with an instant cash valuation! The impact

of this seemed to be that some viewers mistakenly concluded that the countryside

must be strewn with space rocks and that finding one would undoubtedly

pay for a new car. Most of the phone calls I receive quickly turn to monetary

matters: typically I'll be told something along the lines of:

"I found this rock on the beach and I'm certain it's a meteorite.... How much is it worth?"

Sadly, in nearly twenty years selling and lecturing about meteorites I have only once been shown a good candidate. This was a frustrating experience: an archaeologist had found a small, oriented iron while field-walking in the Norfolk Brecks, which he brought along to one of my talks at the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy. As soon as I saw it, I was absolutely certain it was the real thing: I asked the finder if I could borrow it and take it to the Natural History Museum. He refused.

I asked if I could do an on-the-spot nickel test. He refused. I asked if I could at least photograph it..... you've guessed the answer already! So I feel it might be useful to put in print a few guidelines to help recognise a real meteorite and eliminate the usual confusion objects. It's worth reflecting on the fact that 300 tonnes of meteoritic material lands on Earth each day, so there really is a lot of it out there: if you know what you're looking for and can carry out a few simple tests, you might well be lucky! (But, The Meteorite Men notwithstanding, you're unlikely to get a new car out of it!)

The first thing to stress about meteorites is that the great majority are actually quite ordinary-looking: the examples shown in the few books on the subject are generally chosen from thousands just because they are particularly attractive! If you find a glittery, beautifully-marked or shaped rock it won't be a meteorite! (Just a small 'plug': my guide to meteorites - 'Spacerocks' includes a chapter on where you'd have the best chance of finding one!) Here are five ways to help you recognise a real meteorite!

1) Is it attracted to

a magnet? The vast majority of stony and iron meteorites are strongly

attracted to a decent magnet because of the nickel-iron they contain.

Only the very rarest achondrites are not.

2) Does it weigh more than it looks as if it should? For the same reason

as above, meteorites are generally surprisingly dense. Common chondrites

are usually in the density range of 3.0 - 3.7 g/cm3

3) Does it have a fusion crust? A meteorite acquires a thin, black crust

because of the high temperatures generated by friction as it passes through

the atmosphere. This will fairly quickly disappear on exposure to wind

and rain, but a fresh fall should have a sooty, matt surface

4) Does it display flowlines and/or regmaglypts? The frictional forces

mentioned above often sculpt the surface of a meteorite, producing thumbprint-like

depressions called regmaglypts. If the meteorite has orientated itself

in flight, it might also show shallow flowlines where molten rock has

streamed away from the hottest front surface

5) Does it contain nickel? Although nickel-containing minerals are not

rare on Earth, most rocks wouldn't give a positive response to a nickel

test. If you want to test your own finds, you can buy a test kit for less

than £10 at Boots!

The vast majority of

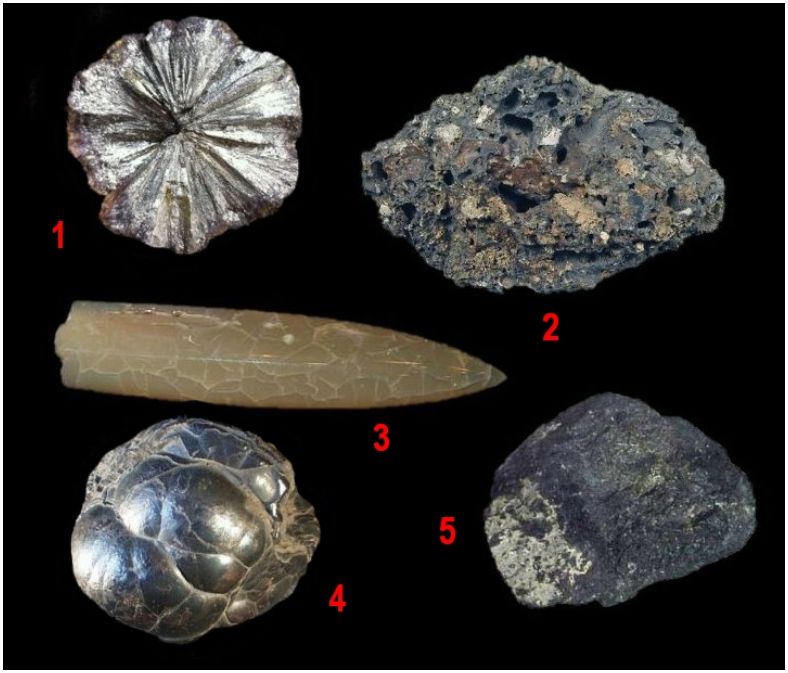

the putative meteorite finds I am shown turn out to be one of the following:

I have put them in order of frequency!

1) Marcasite nodules. Marcasite is a variety of

iron sulphide, FeS2, which occurs quite commonly in limestone and chalk

areas. It formed when hydrogen sulphide released by decaying organic material

reacted with iron ions in ancient seas to produce an insoluble mineral.

This is not ferromagnetic and doesn't test positive for nickel. Most nodules

display beautiful radiating silvery crystals when broken or cut and, with

their golden, lumpy surface look like people imagine meteorites should!

2) Furnace slag. Most people would be surprised to learn that, in times

gone by, iron smelting was carried out in even the most isolated communities.

Once the skill had been brought to the British Isles by the Celts, everyone

wanted iron weapons and tools: it was like the Cold War weapons race 2800

years ago! The smelting process used charcoal, limestone and iron ore,

which left a variety of residues. Some of these are dark, glassy, dense

and attracted to a magnet. The complete absence of chondrules and the

frequent inclusion of bubbles and vesicles are good discriminators.

3) Belemnites. These are the fossil remains of numerous species of prehistoric

squid-like creatures that became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous

Period. They resemble stone bullets with radiating glassy crystals exposed

at the blunt end. They look like what people imagine something from space

should look like, and were, in fact, referred to as 'Thunderstones' in

the middle ages.

4) Haematite. Many naturally occurring minerals and metal ores resemble

meteorites in some way: mammiform haematite, with its curious, glossy

surface, is something I am often shown by a hopeful finder

5) Magnetite. This is ferromagnetic and dense, and can develop a dark

'rind'. It is a very convincing meteorwrong, but, of course, tests negative

for nickel.